Understanding and Choosing File Formats in Photoshop CS and Illustrator CS

Photoshop's File Formats

Each file format that can be generated from Photoshop has its specific capabilities and intended purpose. Most offer one or more options as you save the file. Typically, a supplemental dialog box opens after you have selected a filename, format, and location in Save As.

Format Capabilities: The Overview

Different file formats have various capabilities. Table 3.1 shows a summary of the features of the most important file formats, along with those of some less-common formats for comparison.

The primary formats are discussed individually in the sections that follow.

Outputting to Film Recorders Film recorders (sometimes referred to as slide printers) can be considered printers. However, instead of using paper, they print to photographic film. The most common recorders typically print to 35mm slide film. High-end professional models can print to negative as well as transparency film and can handle medium- and large-format film. Recorders designed for 35mm slide film often produce foggy images when photographic negative film is used. Images are often printed to slides for presentation purposes and printed to negative or positive for printing and archiving. Graphic images to be output to film need to be measured a bit differently. Most film recorders measure resolution as a series of vertical lines across the film. The standard resolutions are 4,000; 8,000; and 16,000 lines. Note that these are not "lines per inch" but rather total lines. Each line represents a dot. The higher the number, the more information sent to the film. The sharpness of the output can vary widely among film recorders of the same resolution. One recorder may use 4,000 lines on a cathode ray tube (CRT) measuring 4 inches wide. Another might place 4,000 lines on a 6-inch CRT. The actual size of the dots (measured in millimeters) can also vary from recorder to recorder. As the image is projected onto the CRT, each dot "blooms," or spreads. The more overlap, the softer the image. Typically (but not always), larger CRTs have less overlap. However, a smaller dot on a 4-inch CRT might produce a sharper image than a larger dot on a 6-inch CRT. Another feature of film recorders is 33-bit or 36-bit color. This feature allows for a wider range of colors, often more than the source program can produce. Images being recorded to film almost always are RGB. The exceptions are usually CMYK images that are being archived or must be duplicated from film. Depending on the film recorder's software, Photoshop can print directly to a film recorder, as it would to an imagesetter, laser printer, or inkjet printer. The film recorder is selected just as you would select a printer. The command File, Export is used with some film recorders. In other cases, the image must be prepared to be opened in or imported into a program that serves as the interface with the recorder. Among the most common file formats required are TIFF, EPS, BMP, PICT, and JPEG. PostScript is often an option on film recorders. The documentation of many film recorders suggests appropriate sizes for images to be output in terms of file size. For example, the documentation may recommend that a 24-bit image be 5MB to fill a 35mm slide. If the image will occupy only part of a slide (in a presentation, for example), the file size can be reduced proportionally. However, when you're preparing an image for a film recorder, it's better to know the actual addressable dimensions, in pixels. This is the number of pixels needed for an exact fit onto the film. A number of popular slide printers use the dimensions 4,096x2,732 pixels for 35mm film. When you're working with film recorders to produce images that fill a frame, the aspect ratio is important. The ratio for 35mm film is 3:2. Film called 4x5 actually has an aspect ratio of 54:42, and 6x7 film is 11:9. (By convention, the larger number comes first when you're discussing aspect ratios. The names of the film sizes list width before height.) If an image is not proportioned properly, you can resize it or add a border. When you're working with presentation slides, a border is often preferable to a blinding white reflection from the projection screen. Some digital film recorders are designed to use 35mm or 16mm movie film. These cameras require aspect ratios appropriate for the film being used. Table 3.1 Capabilities of Key Raster File Formats Format Clipping Paths Alpha Channels Spot Channels Paths Vector Type Layers Primary Use PSD Y Y Y Y Y Y General PSB1 Y Y Y Y Y Y Oversized images BMP Y2 Y N Y N N RGB DCS 2.0 Y Y Y N N N Print EPS Y N N N Y3 N Print GIF N4 N N N N N Web JPEG Y N N Y N N Web/archive JPEG 2000 Y Y Y N N N Print/archive PCX Y N N Y N N RGB PDF Y Y Y Y Y3 Y (Various) PICT N Y N Y N N RGB Pixar Y Y N Y N N Video PNG Y N N Y N N Web Raw5 Y Y Y Y N N Photo SciTex* Y N N Y N N Scans Targa Y N N Y N N Video TIFF Y Y Y Y Y6 Y6 Print WBMP N N N N N N Web

1 - In Photoshop, PSB is also referred to as Large Document Format.

2 - Clipping masks are stored but not used by most other programs. Adobe InDesign does read the clipping path.

3 - Type and shape layers are rasterized if the file is reopened in Photoshop.

4 - Transparent background can be maintained in GIF.

5 - Files are saved as Photoshop Raw, but Photoshop CS is capable of opening Camera Raw files from most digital cameras.

6 - TIFF advanced mode preserves layers.

Photoshop CS ships with optional plug-ins for a variety of file formats that are not needed by the vast majority of Photoshop users (see Figure 3.11). Should you need to work with one or more of these formats, drag the plug-in into the File Formats folder of Photoshop's Plug-ins folder. The next time you start Photoshop, the file format will be available.

Photoshop (.psd)

Photoshop's native file format supports all the program's capabilities. Files in this format can be placed in the latest versions of InDesign and GoLive as smart objects and can be opened in Adobe Illustrator. This is the default file format. Most workflows (but not all) benefit from maintaining a file in Photoshop format until it's time to create a final TIFF, EPS, JPEG, or other file. It's also usually a good idea to maintain the original image, with editable type and layers, for future use.

Figure 3.11 Look for these plug-ins in the Optional Plug-ins folder, inside the Goodies folder, on the Photoshop CD.

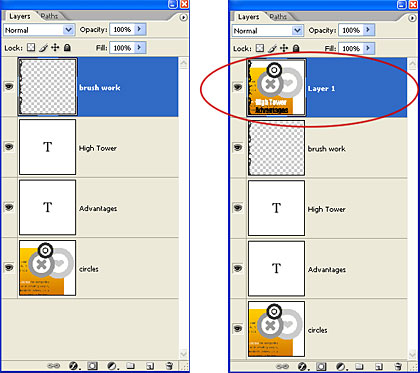

When saving in Photoshop format, you can see that the Save As dialog box indicates which features are used in the image (see Figure 3.12). If a check box is grayed out, that feature is unused. If you uncheck a box, the file is saved as a copy. If you disable a feature (layers, for example) and save the image as a copy, when the image is reopened, that feature is goneno more layers.

Figure 3.12 Selecting the As a Copy check box without changing other options simply appends the word copy to the original filename.

Large Document Format (.psb)

New in Photoshop CS is the capability of saving truly huge images. In earlier versions of Photoshop, the maximum image size was 30,000 pixels by 30,000 pixels. The new PSB file format can handle images as large as 300,000x300,000 pixels. Other than the maximum image size, the PSB file format is functionally similar to the PSD (Photoshop standard) file format.

NOTE Remember that Photoshop's Large Document Format (PSB) is not available until you enable the feature in the File Handling pane of Photoshop's Preferences dialog box.

TIP If you have a very large image that you need to use with a program other than Photoshop, use TIFF. TIFF supports the maximum image dimensions allowed by Photoshop and file sizes as large as 4GB.

Photoshop will remind you that the PSB file format is compatible only with Photoshop CS (see Figure 3.13). Other programs and earlier versions of Photoshop will not recognize the format.

Figure 3.13 Any file can be saved in the PSB format, but it won't be readable in any program other than Photoshop CS. That's another good reason to have this reminder.

CompuServe GIF

GIF is a common Web file format, suitable for illustrations and other images with large areas of solid color and no or few gradients or blends. Many logos and cartoons, as well as Web navigation items, such as banners and buttons, are appropriate for GIF. This file format is not appropriate for most photographs and other continuous-tone images because it can record a maximum of only 256 distinct colors. (A photograph might have thousands or millions of individual colors.) Although very small and adequately detailed thumbnails of photographs can be created as GIFs, a continuous-tone image typically suffers from posterization. When areas of similar (but not identical) color are forced into a single tint, the image quality can suffer severely.

The color table (the list of specific colors included in the image) is controlled through the Indexed Color dialog box. This box opens after you select the CompuServe GIF file format, a name, and a location for the file and then click OK.

For full information on the color options available for GIF files, see "Indexed Color," in Chapter 5, "Color, in Theory and in Practice."

Among GIF's capabilities are interlacing and animation. When a GIF image is interlaced, a Web browser displays every other line of pixels, first, and then fills in the balance of the image. This allows the Web page's visitor to see the image loading, giving the impression that progress is being made and that the image is loading faster. Animated GIFs are created in ImageReady.

Animated GIFs are discussed in Part IV, "ImageReady." See Chapter 23, "Creating Rollovers and Adding Animation."

The GIF format supports transparency in a limited way: A specific pixel can be opaque or transparent. You cannot have any pixels that are partially transparent in a GIF image. If the image is on a transparent background, you need only select the Transparency check box in the Indexed Color dialog box (see Figure 3.14).

You can also specify a color to be made transparent by using the Matte options in the Indexed Color dialog box. All pixels of the specified color then become transparent, regardless of location in the image. Dithering allows an image in Indexed Color mode to simulate more colors than are actually contained in the color table by interspersing dots of two or more colors.

GIFs can also be created with Save for Web. See Chapter 22, "Save for Web and Image Optimization."

The GIF standard is maintained by CompuServe, and software that creates or displays GIF images must be licensed by Unisys. (The licensing fee was paid by Adobe, and part of Photoshop's purchase price goes to the licensing.)

Figure 3.14 The Indexed Color dialog box opens automatically when you use Save As to create a GIF.

Photoshop EPS

PostScript is a page description language developed by Adobe, and it was at the heart of the desktop publishing revolution of the 1990s. An Encapsulated PostScript (EPS) file can contain any combination of text, graphics, and images and is designed to be included (encapsulated) in a PostScript document. EPS files contain the description of a single page or an element of a page.

EPS is typically used for elements to be included in a page layout or PDF document. Because PDF files can be designed for onscreen display as well as print, EPS supports the RGB color mode in addition to the CMYK and Grayscale modes. EPS files cannot be displayed by Web browsers (although they can be incorporated into PDF files, which can be shown through a browser plug-in).

One of the greatest advantages of EPS as a file format is the capability of including both raster and vector data and artwork.

To learn more about the difference between raster and vector images, see Chapter 4, "Pixels, Vectors, and Resolutions."

EPS supports all color modes, except Multichannel, and it does not support layers or alpha and spot channels. (The DCS variation of EPS supports both spot colors and masks and is discussed separately, later in this chapter.) The EPS Options dialog box, shown in Figure 3.15, offers several options.

The Preview option determines which imageif anywill be shown in the page layout program where you're placing the file. The preview doesn't normally have any effect on the printed image and is used for onscreen display only. Windows offers only None and TIFF as preview options. Here are the options offered by other platforms:

None No image preview is saved. Although Photoshop's File Browser can still generate a thumbnail, files placed into a page layout document may show on the screen as a box with diagonal lines.

TIFF (1 bit/pixel) A black-and-white (not grayscale) version of the image is shown in a page layout document.

TIFF (8 bits/pixel) A color version of the image is displayed onscreen in page layout programs. This option provides a reasonably accurate preview and is cross-platform.

Macintosh (1 bit/pixel) A black-and-white PICT preview is included with the EPS file. The PICT file format is designed for use on Macintosh systems but can be used for Windows programs as well.

Macintosh (8 bits/pixel) A color PICT preview is prepared.

Macintosh (JPEG)A JPEG preview is used, which can reduce the file size but also the compatibility.

Figure 3.15 Note in the Save As dialog box that the warning triangles indicate which features are not supported by the EPS file format.

The Encoding options include ASCII, Binary, and JPEG. ASCII is cross-platform and compatible with virtually all page layout programs. Binary is a Macintosh encoding system, and it can produce smaller files. JPEG encoding produces comparatively tiny files but uses lossy compression (which can result in image degradation) and is not compatible with all page layout programs. In addition, JPEG encoding can prevent an image from properly separating to individual color plates. ASCII is certainly the safest choice when the image will be sent to a printer or service bureau.

Halftone screens and transfer functions are established through the Print Preview dialog box. Screen frequency, angle, and shape can be established for each ink. These criteria determine the distribution and appearance of the ink droplets applied to the paper. The transfer function compensates for a miscalibrated imagesetter.

CAUTION Never change the halftone screen settings or transfer functions unless specifically instructed to do so by your printer or service bureau. Incorrect data can result in project delays and additional costs.

PostScript Color Management is available only for CMYK images outputting to devices with PostScript Level 3. This option should not be selected if the image will be placed into another document that itself will be color managed.

When the image contains unrasterized type and/or vector artwork or paths, select the Include Vector Data check box. When you're outputting to a PostScript device (such as a laser printer or imagesetter), the vector outlines will be preserved and the artwork will print more precisely. You need not include vector data when outputting to an inkjet printer.

CAUTION The advantages of vector type and artwork are lost if an EPS file is reopened in Photoshop. Photoshop must rasterize an EPS file to work with it. If you've saved vector data, do not reopen the EPS file in Photoshop.

Checking Image Interpolation allows a low-resolution image to be upsampled (resampled to larger pixel dimensions) when printed to a PostScript Level 2 or 3 printer. Increasing the resolution during printing helps smooth edges and improve the general appearance of low-resolution images, but this could introduce a slight out-of-focus appearance. If the output device isn't PostScript Level 2 or higher, this option has no effect.

For more information on upsampling, see "Two Types of Resampling," in Chapter 15, "Image Cropping, Resizing, and Sharpening."

JPEG

Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) is technically a file compression algorithm rather than a file format. The actual file format is JFIF (JPEG File Interchange Format), although JPEG is more commonly used. JPEG supports Grayscale, RGB, and CMYK color modes and can be used with files more than four times as large as Photoshop's 30,000x30,000 pixel maximum. JPEG does not support transparency, alpha channels, spot colors, and layers. Paths can be saved with a JPEG file, including clipping paths (although most programs can't use the clipping path, with the notable exception of InDesign). Type is rasterized when a file is saved as JPEG.

JPEG is commonly used on the Web for photographs and other continuous-tone images in which one color blends seamlessly into another. Because of its support for 24-bit color (in RGB mode), JPEG is far better than GIF for displaying the subtle shifts in color that occur in nature. (Rather than GIF's maximum of 256 distinct colors, JPEG files can include more than 16.7 million colors.) JPEG is the most common file format for digital cameras because of the outstanding file size reduction capabilities.

NOTE It's important to keep in mind that JPEG is a lossy compression system. Image data is thrown away when the file is saved. When the image is reopened, the missing data is re-created by averaging the colors of surrounding pixels. For more information, see "Resaving JPEG Images," later in this chapter.

When you choose JPEG as the file format and click OK, Photoshop's Save As dialog box is replaced with the JPEG Options dialog box (see Figure 3.16). You can select a matte color, a level of compression, and one of three options for Web browser display.

JPEG files can also be created with the Save for Web option. See Chapter 22, "Save for Web and Image Optimization."

Figure 3.16 The bottom of the dialog box shows the estimate of the amount of time it will take, under optimal conditions, for the file to download at a given modem speed at the selected quality setting.

Simulating Transparency in JPEG Files

Although JPEG does not support transparency, you can choose a matte color that will help simulate transparency in your image. From the Matte pop-up menu in the JPEG Options dialog box, choose a color that matches the background of the Web page into which the image will be placed. By replacing transparent areas of the image with the selected color (rather than just flattening to white), you cause those areas to match the Web page's background (see Figure 3.17).

NOTE With the Preview check box selected in the JPEG Options dialog box, you'll see the matte applied to the image. If you're saving the image as a copy (which you will if the image has a transparent background), remember that the matte is applied only to the copy, not the original image.

Figure 3.17 The Photoshop image is shown at the top. To the left, it has been saved as a JPEG with a red matte and placed into a GoLive document with a red background. On the right is the image as it appears in a Web browsera JPEG duck surrounded by "transparency."

Optimization Options

The cornerstone of the JPEG format is image optimization. The JPEG Options dialog box presents you with the tools to strike a compromise between file size and image quality. The Preview check box enables you to monitor changes to the image's appearance. The Image Options slider ranges from 0 (very small file, possibly substantial quality loss) to 12 (large file, very littleif anydamage due to file compression). The Quality pop-up menu offers Low (3), Medium (5), High (8), and Maximum (10) settings. Figure 3.18 shows a comparison of file sizes and file quality, using the duck image from the previous figure. The chart shows file format, compression type or level, and file size as reported by Mac OS X's Get Info command. (Different images might produce substantially

CAUTION When preparing images for the Web, you should generally make final decisions based on the images' appearance at 100% zoom. With the exception of SVG images, Web browsers can display images only at 100%, so base your decisions on how the pictures will look to the Web page's visitor.

NOTE Different programs use differing JPEG quality/compression scales. Photoshop uses a 13-step scale (012), Illustrator uses 010, and Save for Web works with 0%100%.different results.)

Figure 3.18 From left to right, the three images show JPEG quality settings of 12, 5, and 0. Note the substantial image quality degradation at the lowest quality setting.

Format Options

The Format Options section offers three JPEG format versions from which to choose:

Baseline ("Standard") This is the most widely compatible version of JPEG, which can be displayed by all graphics-capable Web browsers. It's also the version to use for non-Web JPEG files.

Baseline Optimized Optimized JPEG can produce better color fidelity but is not compatible with all older Web browsers.

ProgressiveLike interlaced GIF files, progressive JPEG files appear in stages in a Web browser, providing visual feedback and the illusion of speed to the Web page's visitor. You can elect to have the image appear fully in three, four, or five passes. (Three passes is usually adequate.) Progressive JPEG files are typically (but not always) slightly larger than baseline (standard) versions of the same files.

At the bottom of the JPEG Options dialog box is an area that shows the size of the file that will be created with the selected options as well as how long such a file will take to download. The pop-up menu enables you to select modem speeds ranging from 14.4Kbps to 2MBps.

JPEG/JFIF became an ISO standard in 1990. Baseline JPEG is in the public domain, but many variations are patented and licensed. Variations of lossless and near-lossless JPEG are under development.

Resaving JPEG Images

Because JPEG is a lossy compression scheme (some data is thrown away during compression), it's generally understood that files should be saved in the format only once (if at all). Resaving a JPEG file in JPEG format sends the image through the compression process again, possibly resulting in damage to the image's appearance because of the second round of data loss.

With the booming popularity of digital cameras, more and more images are being captured as JPEGs. Completely eliminating JPEG as a file format for resaving these images (and JPEGs created for the Web) after editing is unfeasible. To best understand how to avoid damaging an image when resaving it as a JPEG, you should know a little about how JPEG compresses.

Lossy compression, such as JPEG, can produce far smaller file sizes than lossless compression. That's because some image information is actually thrown away during the compression process. When the image is reopened, the existing data is averaged to re-create the missing pixels. However, the cost is image quality (see Figure 3.19).

To the left is the original. In the middle, saving at the highest quality produces little degradation. On the right, a JPEG Quality setting of 1 greatly reduces the quality of the image. Zooming in to 800% shows one key aspect of how JPEG works. In the low-quality version of the image, JPEG's distinctive 8x8 blocks of pixels are visible (see Figure 3.20). Colors can be averaged or patterns determined based on the content of the blocks.

Because JPEG uses blocks of pixels to compress an image, cropping becomes important. If you must crop an image that has already been substantially compressed with JPEG, any cropping from the top and left should be in increments of 8 pixels. Two copies were made of the image saved at JPEG Quality 1 (see Figure 3.21). One copy (left) was cropped exactly 8 pixels from the top and 8 pixels from the left. The second copy (right) had 4 pixels cropped from the top and left. Both copies were then resaved at JPEG Quality 1.

Figure 3.19 As you can see, the image on the right (saved at Quality 1) has a much degraded appearance compared to the original (left) and the image saved at Quality 12 (middle). However, the lower-quality image has a file size about one-third that of the higher-quality image.

Figure 3.20 An image is broken down into these 8x8 pixel blocks, starting from the top-left corner.

Perhaps the most precise way to crop an image in increments of 8 pixels is to use the Canvas Size dialog box. It not only allows you to specify an exact pixel size, but the Relative check box even eliminates the need to do mathselect the check box and enter a negative number to reduce the canvas size (see Figure 3.22).

Another technique for preserving image quality when resaving a JPEG file as a JPEG file is to use exactly the same compression setting as originally used. If the original quality/compression setting is known, and if the image is being recompressed in the same program, then this technique is valid. However, keep in mind that different programs use different "scales" of JPEG compression. Saving a JPEG file at Quality 4 in Photoshop is not the same as saving as Quality 4 in Illustrator, nor is it the same as using 40% in Save for Web. Also, there is no set formula to translate between compression settings from a digital camera and Photoshop.

Figure 3.21 The image that was cropped in increments of 8 pixels (left) bears far more resemblance to the original (top). On the right, the image that was cropped in increments of 4 pixels looks much blurrier.

Figure 3.22 The grid, called the proxy, determines from where the canvas will be reduced or enlarged. If you're cropping from the center, remember to work in increments of 16 pixels (8 pixels for each edge).

When minimizing additional image degradation is important, consider resaving JPEG files at High or Maximum Quality, especially if the image has been cropped. The file size might be somewhat larger than the original JPEG, but quality will be maintained.

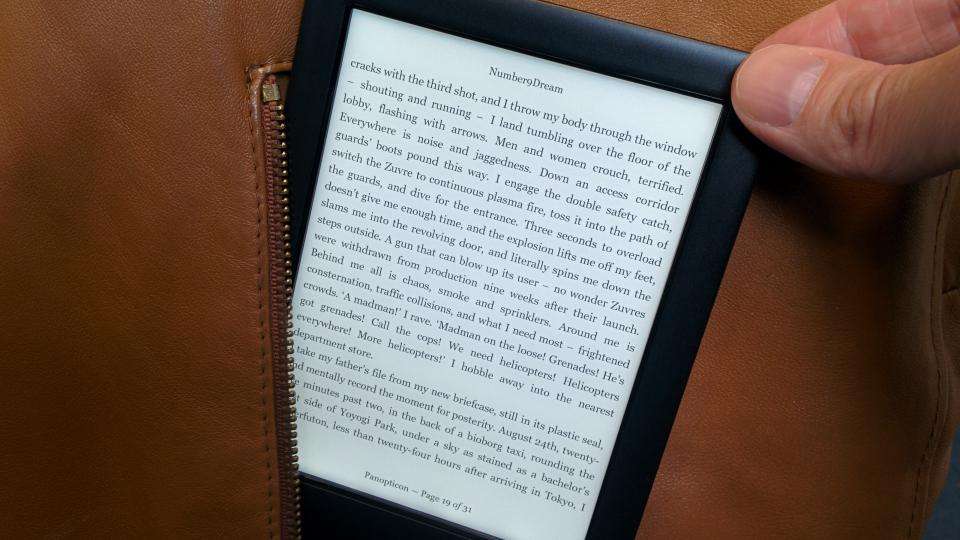

If you use a digital camera, a little experimentation can help you determine which quality setting you should use. In the example shown in Figure 3.23, the image in the upper right was taken at SQ (Standard Quality), which captures 640x480 pixels for this camera. To the left is the same scene, shot at HQ (High Quality), which produces an image 1,600x1,200 pixels, compressed at approximately the equivalent of using JPEG Quality 7 in Photoshop. The image in the lower right was shot at SHQ (Super High Quality), 1,600x1,200 pixels, minimal compression.

The two larger JPEG images are cropped to about 469KB when open in Photoshop. The original images as captured were 480KB (left) and 956KB (lower right). With the minimal difference in image quality and the substantial difference in file size between HQ and SHQ, for most purposes the more practical setting for this camera is HQ. Your camera may differ.

Figure 3.23 The two lower images are zoomed to 300%. The upper-right image, because of the smaller pixel dimensions, is zoomed to 700%.

Photoshop at Work: Controlling JPEG Compression

JPEG is an important file format when you consider the number of such images on the Internet and those taken with digital cameras. The lossy compression algorithm that JPEG uses is worth exploring. To practice controlling JPEG compression, follow these steps:

Open an image, any image, in Photoshop. Use the menu command File, Save As and then select JPEG as the file format. Use an image quality value of 0 and save the file to your desktop. Close the open file and use the menu command File, Open to open the file you just saved. Click the leftmost button at the bottom of the History palette to create a copy of the open image. Save this copy, appending "-1" to the name. Again, use JPEG quality 0. Close and reopen the 1 file. Position the two windows next to each other and zoom in 500% on an area of detail. Compare the two. Although neither looks good, they should be nearly identical. Use the menu command Image, Canvas Size. Click in the lower-right corner of the proxy (the 3x3 grid labeled Anchor). Switch the unit of measure to pixels and then input a height and width, each 4 pixels smaller than the original value. Click OK. Save the file as JPEG again, using the lowest quality setting. Close and reopen the image. Zoom in 500% and compare this version to the original.

You should see that saving the same image at the same setting doesn't cause much harm, but using a low compression setting after cropping an image that has already been compressed with JPEG can cause severe quality reduction.

NOTE To create a JP2-compatible file, you must check the box to include the document's color profile in the Save As dialog box. If you don't include the ICC profile, the JP2 Compatible box will be grayed out in the JPEG 2000 window.

JPEG 2000 (.jpf)

JPEG 2000, an improved variation of the JPEG file format, is now supported in Photoshop. Although this format is used for both print and the Web, most Web browsers require a plug-in to display JPEG 2000 images. You'll need to install the JPEG 2000 plug-in from the Photoshop CS CD to use this format.

Photoshop opens files in the extended JPEG 2000 format (JPF), but it can also create JPF files that are compatible with the JP2 format for JPEG 2000. (The file extension remains .jpf, regardless of whether the file is JP2 compliant or not.) The JPF format is more flexible than JP2, but fewer Web browser plug-ins are available. JP2 files will be 1KB larger than their JPF counterparts.

Among the advantages of JPEG 2000 over the earlier version of JPEG are transparency and lossless compression. You also have some control over what metadata is included with the file and how the image will appear in a browser as it downloads.

The JPF format supports RGB, CMYK, and Grayscale color modes, in either 8-bit or 16-bit color. Alpha channels, spot color channels, and paths are retained. Layers are merged when saved as JPF.

To create a JPF file, select the file format in the Save As dialog box, name the file, and choose a location. If desired, check the boxes to include the document's ICC profile (mandatory if JP2 compatibility is required) and spot or alpha channels. Then click Save. The JPEG 2000 window will open (see Figure 3.24).

Figure 3.24 More than just a dialog box, the JPEG 2000 window is reminiscent of a less-complex Save for Web window. You can resize the window by dragging the lower-right corner.

The JPEG 2000 window consists primarily of a large preview area to the left and settings options to the right. Here are the principle features of the JPEG 2000 window:

Standard Zoom and Hand tools are available in the upper-left corner.

The lower-left corner offers a zoom pop-up menu, with 10 preset zoom factors, ranging from 3.125% to 1600%.

The File Size field enables you to select a target size for the file. This option is not available if lossless compression is used.

The Lossless option prevents degradation of the image caused by lossy compression. Selecting Lossless will produce larger file sizes.

Fast Mode improves the speed of the JPF file encoding, without harming the image. The File Size option is grayed out when Fast Mode is selected, although the actual file size can still be changed using the Quality slider or entering a value in the field.

The Quality slider is used to determine the amount of compression applied to the file. It is not available when the Lossless box is checked because it controls only the lossy compression scheme. Like Save for Web, the Quality slider's values range from 1 to 100.

You can elect to include metadata with the file. Depending on the choices made in the Advanced Options, you can include the image's metadata as XML (JPEG 2000 specific), XMP (Photoshop's File Info format), and/or EXIF data (from a digital camera).

The image's ICC profile will be included, provided all three of the following boxes are checked:

Embed Color Profile (in the Save As dialog box)

Include Color Settings (in the JPEG 2000 window)

ICC Profile (in the Advanced Options dialog box of the JPEG 2000 window)

The Include Transparency option is only available when the image is on a transparent background. Layers will be merged upon saving, but the image will not be flattened.

JP2 compatibility increases the file size by 1KB, but a wider variety of plug-ins will be able to open the file.

The options accessed by clicking the Advanced Options button provide you with a choice of what types of devices you want the file to be compatible with (currently there is only one choice), the type of lossy compression "wavelet" you want to use, Integer (more consistent throughout the image) or Float (a bit sharper), the Tile Size setting (generally 1,024x1,024 is appropriate), the metadata format, and the type of ICC profile(s) to include (standard or the restricted profiles intended for cell phones and wireless devices). The Float compression scheme, available only for lossy compression, is useful for images with lots of fine detail, but it can create artifacts along edges. The tile size, which determines the areas of each "block" used for compression, is generally best left large. However, images for wireless Web access may benefit from a smaller tile size. Also, although the JPEG 2000 standard implies that a "restricted" ICC profile should be embedded in every JPF file, the devices for which the restricted profiles are intended (cell phones and PDAs) are not generally color managed...yet.

As shown in Figure 3.24, you can specify how you want the image to display as it downloads using the Order pop-up menu. The options are Growing Thumbnail (a small image appears, then larger and larger versions of the image appear until the image is fully loaded), Progressive (the image starts fuzzy and then sharpens as it downloads), and Color (a grayscale version appears, which changes to color when the image is finished downloading).

NOTE Keep in mind that if your image is not intended for the Web, the only significant options are in the JPF Settings section of the window. If the file contains one or more alpha channels, a channel can be selected as the "region of interest." The alpha channel determines what areas of the image require the highest quality. Because the Region of Interest option doesn't increase file size, all improvements within the region of interest result in decreased quality outside the region.

The Enhance slider determines how much priority is given to the region of influence. The higher the level, the greater the quality within the area designated by the alpha channel (and the lower the quality outside).

The Download Rate pop-up menu enables you to choose an Internet connection speed that will be "previewed" in the window. You can see how long it will take your image (nominally) to download over a connection of that speed in the field to the left, below the preview area.

The Preview button shows you how your selected optimization order looks. Click the button, and the image will appear in the preview area as it would load into a Web browser.

Photoshop PDF

Adobe's Portable Document Format (PDF) is a cross-platform format that can be opened and viewed in the free Acrobat Reader, available for most computer operating systems. PDF is, at heart, a PostScript file format. Photoshop breaks PDF into two categories: Photoshop PDF and Generic PDF. Both can be opened, but only the former can be created.

Photoshop PDF supports all of Photoshop's color modes, transparency, vector type and artwork, spot and alpha channels, and compression (JPEG or ZIP, except for bitmap images, which use CCITT-4 compression).

NOTE Photoshop can produce only single-page PDF documents and can open only one PDF page at a time. However, the menu command File, Automate, Multi-Page PDF to PSD can be used to create a separate document from each page of a PDF file. In addition, Photoshop CS now offers the command File, Automate, PDF Presentation. Use this command to generate a multipage PDF or a presentation in PDF format from several single-page PDF documents.

The PDF Options dialog box, shown in Figure 3.25, offers a choice of compression schemes as well as several other choices.

ZIP compression is most effective for images with large areas of solid color, and it is also more reliable than JPEG for PDFs that are destined for process printing. (PDFs compressed with JPEG might not separate correctly.) JPEG, however, can produce substantially smaller files (at the cost of image quality).

Figure 3.25 After you select a filename, location, and Photoshop PDF as the file format, clicking OK opens this dialog box.

Photoshop also enables you to use standard PDF security, such as that added to PDFs in Adobe Acrobat (see Figure 3.26). Passwords can be required for opening the document as well as for printing, selecting, changing, copying, or extracting the document's content.

Figure 3.26 Other check boxes in the PDF Security dialog box are made available if they pertain to the file being saved.

PNG

Developed as an alternative to GIF and JPEG for the Web, Portable Network Graphics (PNG) comes in both 8-bit (Indexed Color) and 24-bit (RGB) variations. JPEG's lossy compression and the licensing requirement associated with GIF's compression lead to the demand for an alternative. PNG-8 and PNG-24 are both now widely supported by Web browsers.

The Save As dialog box makes no distinction between PNG-8 and PNG-24, instead using the file's existing color mode. If the image is RGB, PNG-24 is automatically created. If the image is Indexed Color, PNG-8 is used. Grayscale is also 8-bit. (Save for Web allows you to specify whether you want to create an 8-bit or 24-bit PNG file.) Because PNG does not support CMYK, it is not appropriate for commercial printing applications.

Like interlaced GIF and progressive JPEG, PNG files can also be displayed incrementally in a Web browser. After you select the PNG format, name, and location and then click OK, the PNG Options dialog box enables you to make the selection (see Figure 3.27).

Figure 3.27 Interlacing can add slightly to the file's size. It's not necessary with small interface items but is often appropriate for larger images.

Images in Indexed Color mode are comparable in size and appearance when saved as GIF and as PNG-8. PNG-24 cannot match the file size reduction available in JPEG; however, the format does offer transparency (which is not available at all in JPEG) and uses a lossless compression algorithm, thus preserving image quality.

Raw

In Photoshop, it's necessary to differentiate between Raw files saved from the program (Photoshop Raw) and digital camera files being opened in the program (Camera Raw). Many high-end cameras use proprietary versions of the Raw format. Previous releases of Photoshop could not natively open such files. The various camera manufacturers had their own software to open and process the files, from which you could save a TIFF file to open in Photoshop. In early 2003, Adobe released a Photoshop 7 plug-in called Camera Raw for use with the top cameras from Canon, Nikon, Minolta, Olympus, and FujiFilm. That plug-in has been incorporated into Photoshop CS and has some additional capabilities.

Photoshop Raw

The Photoshop Raw file format records pixel color and very little else. Each pixel is described in binary format by color. Because the file doesn't record such basic information as file dimensions and color mode, coordination and communication are important. If incorrect data is entered into the Raw Options dialog box when an image is opened, an unrecognizable mess is likely to result (see Figure 3.28).

When saving an image in the Raw file format in Macintosh, you can specify the four-character file type, the four-character creator code, how many bytes of information appear in a header before the image data begins (if any), and in what order to save the color information (see Figure 3.29). When interleaved, color information is recorded sequentially for each pixelthe first pixel's red, green, and blue values are followed by those three values for the second pixel, and so on. The sequence is recorded as R,G,B, R,G,B, R,G,B.... Noninterleaved order records the red values for all the pixels, then the green values for the pixels, and then the blue values. The sequence is then R,R,R... G,G,G... B,B,B....

Figure 3.28 In the upper left, the image was opened properly. To the right, the Interleaved option wasn't selected. Below, the dimensions were incorrect. If the number of channels or the bit depth is wrong, you'll see a warning that the file size doesn't match.

Figure 3.29 Before saving a file in the Raw format, make sure you know and understand the requirements for the program in which the file will be opened.

Camera RAW

When you select and open an image from a high-end digital camera, Photoshop will, if necessary, launch the Camera Raw plug-in. (Some Raw files can be opened directly in Photoshop.) The Camera Raw plug-in offers very powerful image-adjustment capabilities. Global color and tonal adjustments, sharpening, noise and moiré reduction, and compensation for color fringing caused by chromatic aberration are some of the features of Camera Raw.

NOTE Camera Raw is only available for images in certain Raw format variations. Check for a list of supported cameras and updates to Camera Raw. NOTE If you're comfortable working with the software that came with your camera, you may not want to use Camera Raw. However, if your camera's Raw images launch Camera Raw, take a look at the plug-in's powerful features. You may want to change your workflow.

TIFF

Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) and EPS are the two most widely accepted image formats for commercial printing. TIFF files can be produced directly by most desktop scanners and many digital cameras. The format supports CMYK, RGB, Lab, Indexed Color, Grayscale, and Bitmap color modes. In Bitmap mode, alpha channels are not supported, but they are available in all other color modes. Spot channels are supported, and clipping paths can also be saved with TIFF images to denote areas of transparency.

Photoshop offers a variety of TIFF options, some of which are not supported in other programs. Background transparency, layers, and JPEG compression are three. Additional TIFF options are found in the TIFF Options dialog box, which appears following the Save As dialog box (see Figure 3.30).

Figure 3.30 Some options in this dialog box might be grayed out and unavailable, depending on the image's content.

For maximum compatibility, choose LZW as the compression scheme. ZIP and JPEG are not supported by many programs that use TIFF files. JPEG offers the same 012 scale of quality available in the JPEG Options dialog box.

The Byte Order option determines compatibility with Macintosh or IBM PC computer systems. Because the Mac has no trouble reading the IBM version of TIFF files, that is the safest choice.

Although Photoshop itself doesn't read a TIFF file's image pyramid, the multiresolution data can be saved for other programs, such as InDesign. Image pyramid refers to multiple versions of the same image being stored in one file, each at a different resolution. Photoshop reads only the highest- resolution version of a TIFF file.

If the file contains background transparency, you can elect to save that transparency. As with other advanced TIFF features, the transparency option is not widely supported for TIFF files; however, it is supported by InDesign 2.0. (Remember that this transparency refers to the entire file, not layers above a background layer.)

When a file is saved with layers, you have the option of determining how those layers will be compressed. Because layers can greatly increase file size, ZIP may produce substantially smaller files. You can also choose at this point to disable layers in the TIFF file and save as a copy. In terms of the resulting file, there is no difference between discarding layers (flattening the image) with this option and unchecking the Layers check box in the Save As dialog box.

Because not all other programs can read a TIFF file's layers, Photoshop saves a flattened version of the image as well. Saving layers in TIFF file format triggers a warning message from Photoshop (see Figure 3.31). Because a flattened version of the image is also saved in the TIFF file, the warning can be ignored.

Figure 3.31 If your image is to be used in a program that doesn't support layered TIFF files, discarding the layers can greatly reduce file size with no loss of functionality.

Photoshop DCS

Desktop Color Separations (DCS) is a version of EPS developed by Quark. (The file that's produced has the extension.) The original DCS file format is now referred to as DCS 1.0, whereas an updated, more flexible version is called DCS 2.0.

Photoshop DCS 1.0

Version 1.0 should be used only with older programs that don't read the DCS 2.0 standard. DCS 1.0 supports CMYK and Multichannel modes and creates a separate file for each color channel, plus an optional 8-bit color or grayscale composite. The DCS 1.0 Format dialog box appears after you click OK in the Save As dialog box (see Figure 3.32).

Figure 3.32 These options determine compatibility with page layout programs.

You can elect to save no preview, a 1- or 8-bit TIFF preview, and in Macintosh, a 1- or 8-bit Macintosh (PICT) preview or a JPEG preview. The 8-bit TIFF preview is the most widely supported. In addition to the preview, which is used primarily in dialog boxes, you have the option of including a grayscale or color composite image or no composite at all. The composite is used to show the image when a page layout document is viewed onscreen.

The encoding options include Binary, ASCII, and JPEG. As with EPS files, ASCII is used in Windows and can be read by Macintosh programs, Binary produces smaller files but is Mac specific, and JPEG reduces both file size and compatibility. In addition, JPEG encoding can prevent an image from properly separating to individual color plates. ASCII is certainly the safest choice when the image will be sent to a printer or service bureau.

The Print Preview dialog box offers access to halftone screens and transfer functions for the file. These criteria determine the distribution and appearance of the ink droplets applied to the paper. The transfer function compensates for a miscalibrated imagesetter. Do not make changes to the screens or include a transfer function without explicit guidance from your printer or service bureau.

Photoshop DCS 2.0

DCS 2.0 is a more sophisticated version of Desktop Color Separations. The majority of its options are the same as those described for DCS 1.0. However, DCS 2.0 gives you several options when it comes to what file or files are actually produced (see Figure 3.33).

Figure 3.33 The six Preview options boil down to one file or one file for each channel and a choice of composite image.

If you choose any of the three Multiple File options (no composite, grayscale composite, color composite), one file is generated for each color channel. The four process channels (if present in the image) use the channel's letter for a file extension. Spot channel extensions are numbers, starting with 5. The composite, if generated, will have the extension.

For example, the file "Target" with two spot channels could be saved as DCS 2.0, with multiple files and a color composite. The files generated would be Target.C, Target.M, Target.Y, Target.K, Target.5, Target.6, and

DCS 2.0 should be selected over DCS 1.0 in any circumstance where both are supported. The single file saves disk space and can simplify file exchange and handling.

Where, When and How To Use Them

If you’re a designer, you’d probably know everything about the graphic file formats and use them properly. But even if you’re not a designer, you should still have this information so you can streamline your work process better.

Think about it – how many times have you had your designer looking for that one file while you had no idea what type it was. We’d take a guess and say countless. And let’s face it, situations like these can become quite irritating, right?

So brushing up your knowledge on these graphic file formats, sizes, and other variations would help you make quicker and faster design decisions.

To help you out, we’ve listed the different graphic file formats along with their advantages and disadvantages, so you know when, where, and how to use them.

Now, the graphic files are divided into two main categories. One is the raster graphics, and the other ones are vector graphics.

Let’s look at them one by one.

Raster Graphics

Raster graphics are the ones that are made up of bitmaps. If you’re wondering what bitmaps are, they are pixels made up of fixed resolutions that cannot be changed.

They are mostly used in Photoshop documents. Do keep in mind that you cannot increase the resolution of a raster image to get better quality or clearer image.

The following are the different types of Raster Graphics commonly used in designing.

JPEG or JPG

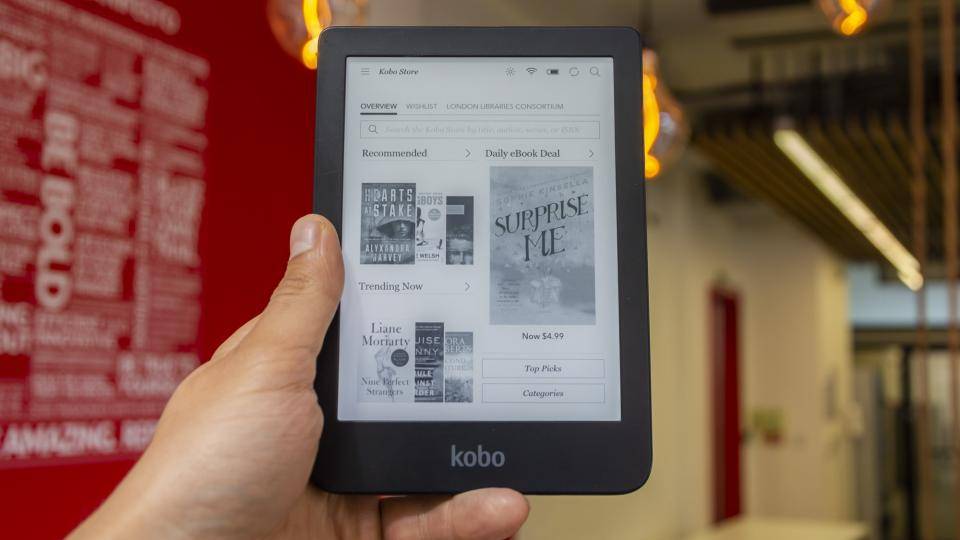

Joint Photographic Experts Group is also commonly known as JPEG. This format is most widely used for pictures and web formats. And are more widely uploaded on the social media platforms as well.

One of the most significant advantages of Jpegs is that it usually takes less space than others because of their smaller size. You can easily send them over to your clients or other designers in your team as well.

However, the disadvantage of using JPEG is that it includes the compression of the image when saved. Every time a jpeg is edited and saved, the picture begins to appear more blur than before. So make sure you keep the editing to a minimum. Adobe Photoshop even provides an option to set the amount of compressing on a JPEG while saving the file.

TIFF

Next is the Tagged Image File Format, also known as TIFF. This format is most commonly used for desktop publishing. Adobe InDesign, a new software introduced by Adobe, also can save files in TIFF format.

The advantage of TIFF format is that numerous pages can be saved at one time and in a single file. Moreover, there is no problem related to the compression and quality of TIFF files, no matter how many times they are saved.

However, due to the hefty amount of information that they can store, there is an issue faced regarding the size of the TIFF files. These files are usually large and can take up a lot of space.

Another disadvantage is that not every software can open TIFF files. You’d need a special kind of file that can only be opened by a particular type of software. Opening it in any other software would show an error.

GIF

Used heavily in social media platforms and texting by people, GIF is known to everyone. It stands for Graphics Interchange Format.

All the short and digital animations that you see are gifs. They are created by combining a series of pictures which are then run on a loop. But while GIF has advantages like being of a tiny size file and can load quickly, it has certain disadvantages.

These disadvantages include the fact that they only support 256 colors. If you have a super vibrant, super bright GIF, you may get a lot more noise in it. Also, once made, GIFs are not easily editable. So if you have to make changes to your GIF, you’ll have to start again.

PNG

PNG files are widely used, like JPEG files on social media and communication platforms. Most of our images and photographs are often in the PNG format too.

It stands for Portable Graphics Format and is an uncompressed image that we all widely encounter over the internet. It was initially created to replace the GIF format but now has standing and use of its own.

They’re relatively easy to use and can be formatted or edited on even Paints on your desktop. Moreover, it has 24bit RGB color palettes and supports transparency that makes it easy to use file type.

PSD

If you work with designers, then you must have heard of it before. PSD is a Photoshop document that is used for making all the creative for social media and other platforms and creating printable material. It is also used for photo manipulation.

PSD allows transparency, which means that the images can be saved without a background and be used anywhere. They are saved in layers, so editing them is relatively easy and smooth. Most importantly, they can be reworked repeatedly without compromising on the image quality.

However, PSD files can be edited only on Adobe Photoshop. Initial work can be done on PSD files and then transferred for further working on any Adobe software, which can be later exported into the final project.

Vector Graphics

Now that we’ve covered Raster Graphic let’s move on to the vector graphic file types. Just as the name suggests, they are made up of vectors. Vectors define the path and fill of each line and color as a logic making it flexible for editing. The most significant advantage of using vector graphics is that you can change them, make the vector large or small, it’s your choice, but there would be no effect on the resolution and quality of the image.

Vectors are considered the best for working since they can be resized without the fear of distortion. People who know and deal with designers tend to take the vector graphics for their work because it’s easier to process than images saved in raster format.

AI

Adobe Illustrator Art or AI images are used for creating vector graphics from scratch. AI being the go-to tool for vector design, it is heavily used for creating logos icons, drawings, typography, and complex illustrations for any medium. AI files are even used for making and editing 2-d models for animation in Adobe After Effects.

The only downside is that using Adobe Illustrator is not a layman’s task and requires quite a bit of learning compared to even Photoshop. On the bright side, AI files can be imported to Figma or Sketch for later use or edits.

EPS

Encapsulated Postscript, or more commonly known as the EPS file, is a graphic file format that is used for vector images.

This vector format is mostly used to design the vectors on a large scale, such as billboards or building posters. You can open, create, and edit the EPS files in Adobe Illustrator or Coreldraw. Like AI files, you can even resize the file without compromising on its quality.

The only drawback is that if you don’t initially create an EPS file as a vector, it can not be edited.

If you work in an office or a professional setup, you must have used a PDF file. But do you know what it is?

Well, PDF stands for Portable Document Format and is most commonly used for documentation processes. These files can not be edited, but you can share them across any software or application.

The best thing about PDF is all modern browsers and mobile devices can open PDF files without any additional software installation. This makes PDF the go-to format for creators to save their vector images (be it AI, EPS or SVG) while sharing with clients.

SVG

SVG stands for Scalable Vector Graphics. They are mostly used to share graphic content on the internet. Almost all modern web browsers like Chrome, Safari and Firefox support SVG files, and that is why many people use them on their websites as well.

You can even download these files and use them as you like.

Sketch

The sketch file type is mainly used for designing the UI and UX of mobile apps and web. They are used for web design purposes. Sketch is a paid online software, but you can import sketch files to online editors like Photopea for quick edits too.

Once you’re done with the design, you can even convert it to any other file type, such as PNG, PDF, or SVG.

Final Word

Knowing these graphic file formats and their use case will not only help you out but would also organize your work more. And while different software and apps support different file formats, GoVisually prides itself in supporting all these graphic file formats.

So, if you want to collaborate with your team over designs, best start using GoVisually from today.

Lastly, if you found this article helpful, let us know your views in the comment section below.

How to Choose the Right Image File Format for Print

How to Choose the Right Image File Format for Print

Excerpted from Real World Print Production with Adobe Creative Cloud by Claudia McCue.

Copyright © 2014. Used with permission of Pearson Education, Inc. and Peachpit Press.

* * *

Appropriate Image Formats for Print

How you should save your raster images is governed largely by how you intend to use them. Often, you will be placing images into InDesign or Illustrator, so you’re limited to the formats supported by those applications. The application may be willing to let you place a wide variety of file formats, but that doesn’t necessarily serve as an endorsement of file format wonderfulness. In the olden days, the most commonly used image formats were TIFF and EPS. However, native Photoshop files (PSD) and Photoshop PDF files are much more flexible, and both formats are supported by InDesign and Illustrator. So, there’s not much reason to use other formats unless you’re handing off your images to users of other applications, such as Microsoft PowerPoint or Word.

TIFF

If you need to blindly send an image out into the world, TIFF (tagged image file format) is one of the most widely supported image file formats. It’s happy being imported into Illustrator, InDesign, Microsoft Word, and even some text editors—almost any application that accepts images. The TIFF image format supports multiple layers as well as RGB and CMYK color spaces, and even allows an image to contain spot-color channels (although some applications, such as Word, do not support such nontraditional contents in a TIFF).

Photoshop EPS

Some equate the acronym EPS (Encapsulated PostScript) with vector artwork, but the encapsulated part of the format’s name gives a hint about the flexibility of the format. It’s a container for artwork, and it can transport vector art, raster images, or a combination of raster and vector content. EPS is, as the name implies, PostScript in a bag (see the sidebar, “EPS: Raster or Vector?”). The historic reasons for saving an image as a Photoshop EPS were to preserve the special function of a PostScript-based vector clipping path used to silhouette an image or to preserve an image set up to image as a duotone. If you’re using InDesign and Illustrator, that’s no longer necessary.

NOTE: When you receive a JPEG image, it’s a good idea to immediately resave it as a PSD or TIFF to avoid further erosion to image content. Repeatedly opening, modifying, and resaving a JPEG can result in compromised quality if aggressive compression is used.

As applications and RIPs have progressed, you’re no longer required to save such images as Photoshop EPS. Pixel for pixel, a Photoshop native PSD is a smaller file than an equivalent EPS and offers support for clipping paths as well as duotone definitions. This doesn’t mean you need to hunt down your legacy Photoshop EPS files and resave them as PSD (unless you’re terribly bored). Just know that unless you need to accommodate someone else’s requirements, there’s no advantage to saving as Photoshop EPS now.

EPS: Raster or Vector?

It may be a bit confusing that there are raster-based EPSs (saved from an image-editing program such as Photoshop) and vector-based EPSs (saved from a vector drawing program such as Adobe Illustrator or Adobe [formerly Macromedia] FreeHand). The uninitiated sometimes think that saving an image as an EPS magically vectorizes it. Not so. Think of the EPS format as a type of container. The pixels within an EPS are no different from those in their TIFF brethren. They’re just contained and presented in a different way.

Photoshop Native (PSD)

In ancient times, the native PSD (Photoshop document) format was used solely for working files in Photoshop. Copies of those working files were flattened and saved in TIFF or EPS formats for placement in a page-layout program. While PageMaker allowed placement of native Photoshop files (yes, really—although it did not honor transparency), QuarkXPress required TIFF or EPS instead. Old habits die hard, and TIFF and EPS have long been the standard of the industry. Not that there’s anything truly wrong with that. However, Illustrator and InDesign can take advantage of the layers and transparency in Photoshop native files, eliminating the need to go back through two generations of an image to make corrections to an original file. Today, there’s no need to maintain two separate images: the working image and the finished file are now the same file.

Photoshop PDF

A Photoshop PDF (Portable Document Format) contains the same pixels as a garden-variety PSD, but those pixels are encased in a PDF wrapper—it’s like the chocolate-covered cherry of file formats. A Photoshop PDF comes in handy on special occasions, because it can contain vector and type elements without rasterizing the vector content, and it allows nondestructive roundtrip editing in Photoshop.

A Photoshop EPS can contain vectors and text, but the vector content will be converted to pixels if the file is reopened in Photoshop, losing the crisp vector edge—so you lose the ability to edit text or vector content. A native Photoshop PSD can contain vector components, but page-layout programs rasterize the content. However, Photoshop PDFs preserve vector content when placed in other applications (see the table below for a feature comparison of common image formats).

Moving to Native PSD and PDF

Is there any compelling reason to continue using old-fashioned TIFFs and EPSs? It may seem adventurous to use such new-fangled files, but workflow is changing. The demarcation between photo-compositing and page layout is blurring, and designers demand more power and flexibility from software. RIPs are more robust than ever, networks are faster, and hard drives are huge. It’s still important to know the imaging challenges posed by using native files (such as transparency), and it’s wise to communicate with your printer before you embark on the all-native path. You’re still at the mercy of the equipment and processes used by the printer, and if they’re lagging a bit behind the latest software and hardware developments, you may be limited by their capabilities.

Bitmap Images

Also called “line art images,” bitmap images contain only black and white pixels, with no intermediate shades of gray. If you need to scan a signature to add to an editorial page or scan a pen and ink sketch, a bitmap scan can provide a sharp, clean image. Because of the compact nature of bitmap scans, they can be very high resolution (usually 600–1200 ppi) but still produce small file sizes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: This 1200 ppi bitmap scan prints nearly as sharply as vector art. It weighs in at less than 1 MB; a grayscale image of this size and resolution would be nearly 10 MB. Magnified to 300 percent, it may look a bit rough, but at 100 percent it’s crisp and clean.

Inappropriate Image Formats for Print

Some image formats are intended primarily for onscreen and Web use. Portable Network Graphics (PNG) images can contain RGB and indexed color as well as transparency. While PNG can be high resolution, it has no support for the CMYK color space.

The Window

s format BMP (an abbreviation for bitmap) supports color depths from one-bit (black and white, with no shades of gray) to 32-bit (millions of colors) but lacks support for CMYK. BMP is not appropriate in projects intended for print.

Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) is appropriate only for Web use because of its inherently low resolution and an indexed color palette limited to a maximum of 256 colors. Don’t use GIF for print.

JPEG (Joint Photographic Experts Group), named after the committee that created it, has an unsavory reputation in graphic arts. Just whisper “jay-peg” and watch prepress operators cringe. It is a lossy compression scheme, meaning that it discards information to make a smaller digital file. But some of the fear of JPEGs is out of proportion to the amount of damage that takes place when a JPEG is created. Assuming an image has adequate resolution, a very slight amount of initial JPEG compression doesn’t noticeably impair image quality, but aggressive compression introduces ugly rectangular artifacts, especially in detailed areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2: There’s good JPEG, and there’s bad JPEG: A. Original PSD B. JPEG saved with Maximum Quality setting C. JPEG saved with lowest quality setting

Each time you open an image, make a change, then resave the image as a JPEG, you recompress it. Prepress paranoids will shriek that you’re ruining your image, and there’s a little bit of truth to that. While it’s true that repeatedly resaving an image with low-quality compression settings would eventually visibly erode detail, the mere fact that an image has been saved as a JPEG does not render it unusable, especially if you use a minimal level of compression. Despite the reputation, JPEGs aren’t inherently evil. They can be decent graphic citizens, even capable of containing high-resolution CMYK image data.

That said, when you acquire a JPEG image from your digital camera or a stock photo service, it’s still advisable to immediately resave the image as a TIFF or PSD file to prevent further compression. However, JPEGs intended for Web use are low-resolution RGB files, inappropriate for print. If your client provides a low-resolution or aggressively compressed JPEG, there’s not much you can do to improve it. Even with the refined Intelligent Upsampling in Photoshop CC, you can only go so far. They’ll find that hard to believe, though, because they know there’s a tool in Photoshop called the Magic Wand. Good luck explaining it to them.